By Dr. Watson Scott Swail, President & Senior Research Scholar, Educational Policy Institute

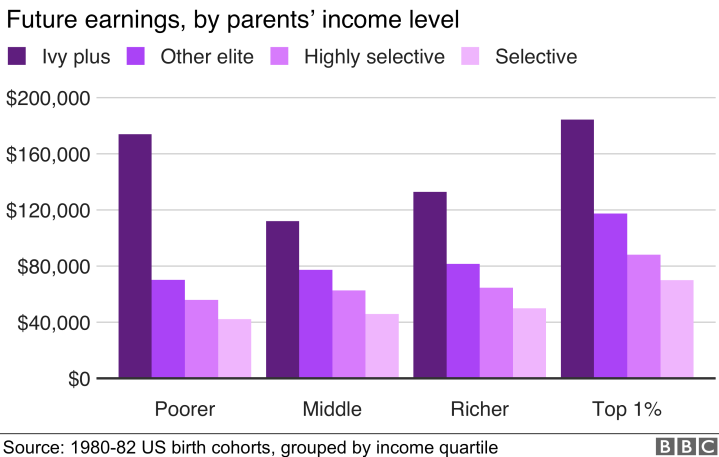

I read an article published this week by Richard Reeves and Katherine Guyot of Brookings titled: “US College Scandal: How much differences does going to a top university make?” There is nothing earth shattering here; it basically buttresses what most of us in the industry have said for years: attending a selective institution has a dramatic impact on social mobility. Data presented in the article illustrate that poor students who go to an Ivy league institution have earnings similar to those from the top 1 percent of family income who go to the same institutions. Personally, I’d like to review the data because I don’t think the ROI is quite so equal between poor and affluent based on all the studies and databases I’ve reviewed over the past several decades. Still, let us assume the point.

What doesn’t make sense is that graduates who were middle or somewhat affluent earned less than poor students. In most analyses that I have either read or conducted, family income and/or socio-economic status have a direct and positive impact on academic and other outcomes. For every dollar in income, there is a direct and positive impact in academic outcome and financial returns. Thus, to see a drop from over $160,000 for poor students to less than $120,000 for middle income and about $130,000 for “richer” students just doesn’t compute. The dataset in question uses a birth cohort of 1980, meaning that these kids would have been in college in 2000 and currently in the workforce for about 15 years. Truth is, the impact could be somewhat different with current cohorts, where we’ve seen the gap between poor and affluent grow in almost every category. But this discussion is largely academic.

The reality is that going to an elite institution has a massive impact on outcomes, and arguably because the networks shift for students. Once in a selective institution, a student’s peer group changes and can follow them into the workforce.

There are certain types of students that attend highly-selective institutions. First are the legacies. They go because their parents or other family members went and receive extra enrollment consideration which puts them ahead of students who may have higher academic credentials (e.g., high school GPA; SAT/ACT scores; AP scores). The second group is that of international students who hold a certain prestige for institutions. Often, if not typically, these students also fall into the third category: students who are academically talented. The internationals fall into this category because only the best of the best apply from around the world. Domestically, students who apply and are admitted to a highly-selective institution are the best of the best. They are the 95th percentile of test takers across the country. With average SAT scores at our best institutions above 1500 points, these students leave others in the dust. The final group are students with special circumstances, including student athletes, musicians, and other artists. It can be argued that there exists a fifth group: low-income, Pell-eligible students. Institutions try and be as equitable as possible, but most of these students still have to fall within the academic wherewithal category. They still have to be academically talented.

We’ve talked often about the advantage that advantage has for students. This isn’t only about White Privilege, as discussed in last week’s Swail Letter. It is about the advantage of income and SES and generations of opportunity. And advantage begets advantage every time. Thus, those who are more affluent have gone to the best public or private schools in the country, have testing coaches, or, as also discussed, have found other “very creative ways” to get their kids into the best schools. This is not to say there does not exist ‘pure intelligence.’ For me, I have gone to school at every level with students that were, for lack of a better word, simply brilliant. This includes a set of twins from my high school in Winnipeg who graduated early and went to Princeton University at age 15. Wear your sunglasses brilliant.

But pure cognitive intelligence does not always rise to the top due to cultural and societal issues. There are poor, bright kids that do not go to college, let alone go to the best colleges. And this happens for a number of reasons, including that their intelligence has not always been developed in a test-worthy manner because their academic development has been significantly hampered by their surroundings and opportunities. Thus, it should not be a surprise that selective institutions still have a small percentage of low-income, Pell-eligible students because the pool of top students who fit the category is quite small. And, of those, a relatively small number of institutions compete for those students.

There is a strong push to get more low-income students into our nation’s best colleges, or at least the most selective colleges (best and most selective aren’t always the same thing, but often are). We have battled a long philosophical challenge about affirmative action in the US about where the line of demarcation exists that separates fairness and equity. Should students who have academic credentials that fall much lower than other students be admitted because of their income or, arguably, their race, compared to other students? Harvard, for instance, could arguably fill every seat in their institution with academically-capable students who were 100 percent non-White or non-Asian. But the students, on average, wouldn’t possess the academic credentials of their White and Asian brethren. Why? Privilege and numbers. White students, in particular, have generation after generation of advantage, as discussed before. And the sheer numbers, as well, with 50 percent of students under 18-years of age being White, compared to 25 percent Hispanic and 14 percent Black.[1] There exists a mathematical advantage for White students that is conflated by the generational issue, let alone affluency.

The Brookings piece illustrates that going to the best schools has positive ramifications for the future for all students, regardless of income. But only so many seats are available for students at these schools and the decision between providing opportunities for the best versus the next-best is a value proposition that smart people can disagree on.

This actually begs a very different question: what about students who go to less-selective institutions? I argue that one of the great issues we have in higher education is the variance in educational quality at our institutions. This is not to say non-selective or less-selective institutions do not provide a high quality of postsecondary education. It does say that, on average, this is the case.

I don’t know if we can effectively remedy the selective institution issue. The discussion herein is light and tackles only the top crust of the issue. It is obviously much more complex than we can dare discuss I this Swail Letter. What we can do is work to improve the quality and opportunities for less-selective institutions, and that is no simple charge. There are many safeguards in the university system via regulation and accreditation, but it is still of interest that, of the thousands of institutions in the US, very few come under scrutiny, let alone reprimanded or even shuttered, for quality issues. Are we that good? Statistics and probability argue not, which calls into question our quality control of higher education.

While we continue to work on how to get more low-income students into better schools, let us perhaps focus on how to make our schools better.

[1] https://nces.ed.gov/programs/raceindicators/indicator_RAA.asp.