by Watson Scott Swail, President & CEO, Educational Policy Institute

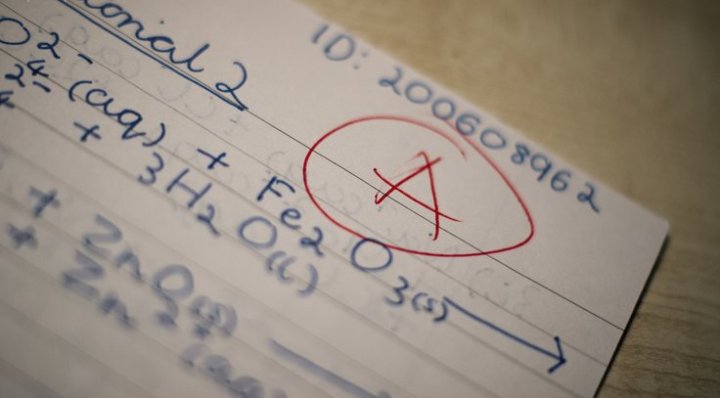

According to a new study to be released in January of next year, the proportion of high school seniors earning an A average in school is increasing even as their SAT score is decreasing. One may suspect that teachers are passing on higher grades to students due to a variety of issues, not the least of which is the pressure to provide higher grades for both student and teacher promotion.

There are two avenues for this trend. First is that more states are looking more seriously at teacher proficiency as a means of performance pay, measured in part by the academic outcomes of their students. The second is that students increasingly need better grades to get into college, especially selective colleges, and also to receive scholarships and grants. So, both stakeholders in this play have something to be gained by higher grades.

A separate finding in a separate study by researchers from Harvard University also found that the modal high school grade is now an A, meaning that more As are given out than any other grade in high school.

While the first question to mind is how this could happen, the real question is why should this matter.

In truth, grades are only remotely useful. Sure, they can tell someone about the proficiency of a student in terms of their knowledge of a subject. But they can also mask that proficiency, too. In many courses, grades can be very subjective when the learning and assessment plans are not collinear.

There is a solution to the grade inflation issue, whether real or perceived: move all high school learning to a competency-based system where students must learn the concepts and skills associated with particular tasks or sections of academic material.

There are a number of positive features of competency-based learning. First, it focuses students on learning and mastery rather than efficiency of time. Students move forward when they obtain a certain level of mastery of a subject area or task. They do not pass on to the next section, or next course, until they have achieved the necessary mastery of these units. The assessment of these skills and knowledge are much easier to produce with accuracy, rather than “sampling” learning by asking particular questions at random that doesn’t effectively cover the material.

Second, teachers find they have a different role in the classroom and become facilitators of learning rather than sages of knowledge. This should be empowering to students and teachers because the roles are very clearly defined. As well, technology can be harnessed in a much more definitive and efficient manner with competency-based learning. Currently, technology is inefficiently used in schools and colleges, even 30-plus years removed from the introduction of PCs began in our K-12 classrooms.

Some states who are actively pursuing competency-based education reforms, including New Hampshire and Ohio. The US Department of Education also showcases school districts around the country who are utilizing this form of teaching and learning.

The argument of grade inflation has been around for a long time. This latest study only fuels more of the inflation fire. We can take care of this in a large way by moving to better teaching and better assessments. Competency-based education: in high school and in college, can help us get there.

Could you comment on how one measures competency with integrity? I’m curious as to how “gameable” a competency measure would be. Could one scrape by with (what used to be) a “C-minus” in order to pass (mastery?) Also, interested in your thoughts as to whether a competency-based progression might lead to competitive students, who formerly had the fixed calendar time, and competed on high scores, switch to a Doogie-Howser (the 13 year old TV M.D.) mode, competing on speed – and perversely learning even more shallowly than now?

Sure. ONe measures competency with integrity by creating quality competencies. Period. Now, in a blog a short piece, there is much to be interpreted, so I understand where you are coming from on this. The trick in CBE is to determine the various levels of competency. For instance, it is clear that not everyone can hit the highest of high notes all the time. So there must be levelling to a degree. A level competency achievement; B, and so forth. But they are straight forward with very little wiggle room for subjective assessment on behalf of the instructor. Also, let us not water down everything in higher education. There does not appear to be a problem in the medical arts right now. It filters people out aggressively. In fact, people are filtered out first via the MCAT, then by the programs themselves, then by their board certifications. Very stringent. Same can be said for many of the professions. But I think it should be equal that someone who is intent on completing a BA in English, for example, should have some level of competency. When I look at a resume/CV from someone and it states their institution and degree, it tells me nothing really about what they can do. Even the GPA is not very helpful because that is relative to the institution, too. I want a list of the actual competencies for the person. Then I know what they can do coming in. Easy? No. Doable? Yes. I appreciate the comment.